(Part 3) Best history of religion books according to redditors

We found 366 Reddit comments discussing the best history of religion books. We ranked the 130 resulting products by number of redditors who mentioned them. Here are the products ranked 41-60. You can also go back to the previous section.

Ya I don't know why this is the top voted comment, it is pretty ignorant. The study of "mushroom" cults is an academic study with ample evidence and it's an interesting field which is actually fairly popular. It was probably the word "Jesus".

References :

http://www.amazon.com/Food-Gods-Original-Knowledge-Evolution/dp/0553371304

http://www.amazon.com/The-Sacred-Mushroom-Cross-Christianity/dp/0340128755

http://www.amazon.com/Persephones-Quest-Entheogens-Origins-Religion/dp/0300052669

http://www.huh.harvard.edu/libraries/wasson/BIOG.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benny_Shanon

http://www.artepreistorica.com/2009/12/the-oldest-representations-of-hallucinogenic-mushrooms-in-the-world-sahara-desert-9000-%E2%80%93-7000-b-p/

this goes on and on and on

I recommend reading Persephone's Quest: Entheogens and the Origins of Religion. I took a course in classical myth by one of the authors, and it was by far the most fascinating course I took.

The difficulty here is that it isn't always clear whether or not the religious explanation ever stood in the place of more pragmatic explanations. To understand what I mean, it's best to look to some competent history of religion and compare it to competent history of science for the same periods. In [The Forge and the Crucible][1], for example, Mircea Eliade looks at the roots of alchemical belief in the origins of metallurgy. He argues -- and I don't see anyway around the logic of his argument -- that a practical understanding of the processes of metallurgy had to have pre-dated their religious interpretation. That is to say, we had to have a practical understanding of the way in which metallurgy worked before it could be significant enough to society to make it an attractive motif for religious interpretation.

The same goes for something like agriculture, and with it astronomy and weather. If you compare what the know of hunter-gatherer cultures with agricultural societies, the religion of the former has markedly fewer references to weather and practically no use for astronomy. The reason is that meteorology and astronomy aren't particularly useful disciplines when you're living mostly off of game. They become much more important once you're practically invested in agriculture, which is why we see the development of astronomy (and later on, astrology) in agricultural societies like those of the Babylonians and Egyptians. The thing about both societies is that they leaned to treat the heavens as regular and consistent processes before they overlaid that knowledge with a layer of religious symbolism. As [Jane Sellers][2] has shown, the Egyptians had long known how to chart the future course of the stars, predict eclipses of the sun, and so forth.

It's unlikely that these cultures developed the religious associations first, stumbling into correct practical knowledge of material phenomenon by sheer luck. Which leads to the general principle that at least some etiological myth develops, literally, after the fact.

That notion is anathema to the argument that a lot of critics of religion would like to bring to bear. They see religion as an attempt to explain the material world, but the historical view deflates that a bit. If nothing else, it's hard to see what etiological myth would add to an already sophisticated understanding of the phenomenon it apparently seeks to explain, particularly if the explanation is raises more questions than it answers. And that's problematic for the science-v.-etiology line of argument, since the underlying premise of that line of attack is that, if religion is an attempt to explain the natural world, providing a better means of explanation will make religion obsolete. But if, as the work of historians like Sellers and Eliade suggests, religion isn't an attempt to explain the natural world, then the the difference between science and religion isn't just one of improved methodology. And, in fact, etiological myths give us much more information about the gods they purport to describe than they do about the phenomenon that presumably explain.

With regard to your request, what I'm getting at is that science may not ultimately have broken down the attribution of certain phenomenon to religion. Ancient farmers likely viewed the heavens in roughly mechanistic terms before they built that knowledge into astrological practice. Ancient metallurgists were using sophisticated techniques to make charcoal and smelt iron before they developed the symbols by which alchemists hoped to turn lead into gold. The advance of scientific knowledge is a stunning and wonderful thing, but if history is any indication, modern day advances are as likely to furnish the symbols of tomorrow's religions as they are to discredit the myths of yesterday.

[1]: http://www.amazon.com/Forge-Crucible-Origins-Structure-Alchemy/dp/0226203905/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1253042808&sr=8-1

[2]: http://www.amazon.com/Death-Gods-Ancient-Egypt/dp/1430317906/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1253043496&sr=1-1-spell

I would encourage you to read Bonhoeffer's Ethics where he goes into his views on this type of stuff. He doesn't talk about his justification of being apart of plots to assassinate Hitler, because Ethics was written before that.

Basically, Bonhoeffer's belief is that, because Christ has already become sin and conquered sin, we don't have to worry about these tough questions. For Bonhoeffer, even if someone needs to do something sinful to save another person, because they are already redeemed in Christ and Christ has taken their punishment, they can rest knowing that.

First of all, can I just say how much I love giving and receiving book recommendations? I was a religious studies major in college (and was even a T.A. in the World Religions class) so, this is right up my alley. So, I'm just going to take a seat in front of my book cases...

General:

Christianity:

Judaism:

Islam:

Buddhism:

Taoism:

Atheism:

Robert Prichard's History of the Episcopal Church is a standard seminary text and a good intro to things on the US side of the pond.

Alan Jacob's biography of the Book of Common Prayer is a nice volume and a quick read.

>He writes on his perspective as a sociologist

So he writes strictly about current trends and patterns, and has nothing to say about historical topics?

When there was a similar outrage over clerical abuse of children in 1643, the church put the accused guy in charge of the religious order teaching children - https://smile.amazon.co.uk/Fallen-Order-Intrigue-Scandal-Caravaggio-ebook/dp/B01MS5OJRK/ref=sr_1_3?ie=UTF8&qid=1550693129&sr=8-3&keywords=fallen+order

I don’t think this is a new issue, and it is nothing to do with any “homosexual agenda”. These so-called men of god are out to conflate homosexuality and paedophilia in an attempt to discredit gay people - whom they have persecuted for centuries.

The Catholic Church has always attracted gay men to their single-sex establishments. The sad thing is they inculcate self-hatred and guilt, which means many of the most outspoken individuals have been the most guilty of abuse. Read about cardinal Keith O’Brien, one of the most vociferous opponents of gay rights at http://www.snapnetwork.org/scotland_scottish_cardinal_resigns

Amazon is a good start. This book is Mircea Eliade could be a title and if you like visuals, buy Alchemy & Mysticism, 576 pages with color images and some explanation. From there on, try to see what it is that interests you.

I would not recommend the version of the Bhagavad Gita /u/wtf_shroom linked to. Understanding the Gita is particularly difficult when it is poorly translated and explained. This one in particular was translated by a British man in the 1800s, when India was a colony and the British were particularly interested in painting Hinduism and Indians as backward.

There are free online translations and commentaries, using modern English. One is here; another is here. These are both Vaishnava translations. This version was used in a very good class at the University of Florida in 2009. That translator is fluent in Sanskrit and also has a Ph.D. in comparative religion from Harvard. He has also studied Vaishnavism with notable Vaishnava teachers.

This brings me to the final reason one should carefully select their version of the Bhagavad Gita. It is an essentially Vaishnava text: in it, Krishna (Vishnu) explains spirituality and the self to his friend and devotee, Arjuna. Vaishnavas worship Krishna/Vishnu as the only God. In the end, Krishna tells Arjuna to "abandon all varieties of religion (or righteousness) and surrender to me." BG 18.66 So, the translation should ideally be by someone who is well-educated as a Vaishnava; someone with a guru, who is linked into the tradition of teachings that have been passed down through the ages. The least ideal arrangement is to have a translation that is made by someone who doesn't understand the tradition, and therefore can't make the translation clear and understandable. Sanskrit is a very context-dependent language, and it is extremely complex: learning the language is not sufficient to qualify a person to translate scripture.

The Real Story of Catholic History: Answering Twenty Centuries of Anti-Catholic Myths by Steve Weidenkopf

A History of Christendom (vol. 1-6) by Warren H. Carroll

History of the Catholic Church by James Hitchcock

Triumph: The Power and the Glory of the Catholic Church by H.W. Crocker Lii

I don't think that I have a book that covers the major writings but I do know of one that covers the major religions. https://www.amazon.ca/gp/product/0745953182/ref=oh_aui_detailpage_o06_s00?ie=UTF8&psc=1

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Religions-Book-Ideas-Simply-Explained/dp/1409324915/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1406671057&sr=1-1&keywords=the+religions+book

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Compact-Worlds-Religions-Encyclopedia-Guides/dp/0745953182/ref=pd_sim_b_13?ie=UTF8&refRID=0PN8VJTH52WYRR0GNEJK

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Religious-Ideas-Really-Need-Know/dp/1848660596/ref=pd_sim_b_36?ie=UTF8&refRID=0PN8VJTH52WYRR0GNEJK

I am fascinated with both topics as well.

Recommendations on anthropology of religion:

Recommendations on philosophy of religion:

http://www.amazon.com/gp/aw/d/0517362457/ref=mp_s_a_1_1?qid=1463301208&sr=8-1&pi=SY200_QL40&keywords=encyclopedia+of+witchcraft+and+demonology&dpPl=1&dpID=51XbwTgzZ0L&ref=plSrch

This book is pretty thorough.

It was suggested I post here. I have to say it's pretty outside of my location and timeframe. Most of my reading is centered around Buddhism and what I know about India that's not political in nature is mostly centered around Buddhism. Even the concepts I know of Hinduism are usually through a Buddhist lens.

What I do know about the development I also can't provide a source. I studied at the Royal Thimphu College and once sat down with a Bengali professor who explained her own dissertation to me about the development of the Varna system in India, which ended up being a primer on "Brahmanism." (Which then led to a long discussion on the inaccuracy of the term "Hinduism" which was developed post-independence as a response to the development of Pakistan for Muslims, India for Hindus. When I presented the irony that "India" and "Hindu" both stem from the "Indus River" which is currently in Pakistan, Runa, aforementioned professor, winked at me and said "Exactly. Hindus are political, Brahmanists are religious." The logic being that Brahmanists derive religious authority from the Brahmin Varna, just as Christians derive religious authority from Christ, and Muslims from submission to God.)

Anyway, I'll just point out some of the books that have helped me in understanding this complex religion and maybe you can go on with your search from there.

Originally I was interested in Wendy Doniger's The Hindus: An Alternative History but found out it was full of selective information and skewed perspectives. I was more interested in a general history of India and fell upon John Keay's India: A History which he describes as "A historiography of India as well as a history." And he does go over developments of Brahmanism threaded with the rise and fall of conquerors through the region.

My introduction to Brahmanism (though he DOES refer to it as Hinduism) was Huston Smith's The World's Religions which doesn't go over the history as much of any of the religions, but is a nice starting point, especially when comparing say Buddhism with Brahmanism, which most people regularly do. It's also a good outliner for the different Brahmanist traditions (or at least the major trends in Brahmanism).

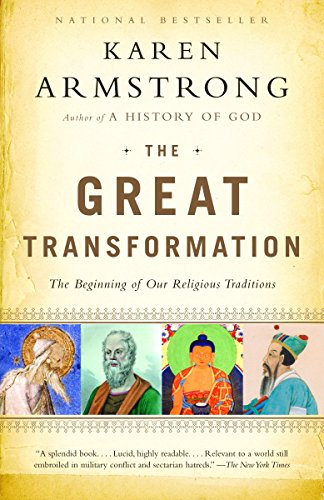

Finally, probably the most accurate to your original question though it has a broader focus and a point to make, Karen Armstrong's *The Great Transformation remains one of my favorite books on the Axial Age in which she covers the religious shifts that occurred more or less simultaneously in Greece, the Levant, India, and China. Of interest to you would be the Vedic response to the growth of Buddhism and Jainism, the development of the Mahabharata, and the changing understandings of the Vedas and Upanishads. It's a pretty great book, and Karen Armstrong can of course lead you further down the path of Indian religious history.

Hope that helps at all.

I just read Graham Schweig translation and I thought it was amazing. He kept it as literal as possible (especially in terms of word order) but still managed to make it clear and poetic.

Bhagavad Gita

He's coming from the Vaisnava tradition, a disciple of AC Bhaktivedanta Swami and with a Harvard degree in Sanskrit and Indian Studies.

For me, the essential verse, summing it all up as it were is 18.65. Check it out for yourself :)

Sure. The Genesis Wheel: https://www.amazon.com/Genesis-Wheel-other-hermeneutical-essays-ebook/dp/B07TT4N5ZZ

And Chariot:

https://www.amazon.com/Chariot-Bethsheba-Ashe/dp/1530524431

Upvote for contributing to the discussion.

> I think it's fair to point the claim these splinter groups are practicing fundamental "mormonism" can be challenged and debated. I think there are many scholars who would compare the two and say they are not comparable.

Care to expand on your argument? The whole concept of fundamentalism is that these groups are rooted in the founding, fundamental doctrines and practices of mormonism. In fact, the fundamentalists have a very strong argument that it is the mainstream church that has strayed/apostatized from the church that Joseph Smith restored and Brigham Young continued. This is how the fundamentalists get converts. A TBM picks up the Journal of Discourses at the DI and they start reading them. They then realize that the modern SLC church has strayed from Joseph and Brigham.

> The reason I point this out is to say the Adam-god doctrine, which is existent after Joseph Smith, is fundamental mormonism is something that can be challenged, because the membership broadly never accepted it.

I'll point you to this. I never knew how important the Adam God doctrine was to 1) Brigham Young, and 2) modern mormon fundamentalists/polygamists.

https://www.amazon.com/Understanding-Adam-God-Teachings-Comprehensive-Materials-ebook/dp/B07BB6H62Z/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1536256214&sr=8-1&keywords=drew+briney+adam+god

Happy happy cake day! :3

1

3

5

6

7

8 NSFW

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

19

20

Bonus: This?

The modern world is a fun topic in philosophy. Stephen Kotkin called modernity a geopolitical necessity rather than simply cultural evolution.

Philosophize This podcast on the problems of modernity: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Svp959mvhn0

Some philosophers who argued against modernity:

Rene Guenon: https://www.amazon.com/Crisis-Modern-World-Collected-Guenon-ebook/dp/B075DCWKBP

If you're feeling controversial Julius Evola: https://www.amazon.com/Revolt-Against-Modern-World-Julius/dp/089281506X

I recently came across Augusto Del Noce (haven't read him yet): https://www.amazon.com/Crisis-Modernity-Augusto-Del-Noce-ebook/dp/B00QMWI2C8/?tag=firstthings20-20

"The album's track listing and re-illustrated symbols from Barbara G. Walker's The Woman's Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred Objects were then positioned around the edge of the collage." - [Source 1](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In_Utero_(album), Source 2

Also, if we are making suggestion for what to read, I strongly suggest Nicholas Wade's three somewhat recent books on the evolution of religions, cultures, and modern humans. It might allow you to take a broader view of what seem like neat and narrow issues. The audiobooks are well narrated if you prefer those.

http://www.amazon.com/Before-Dawn-Recovering-History-Ancestors/dp/014303832X/ref=la_B001H6WF40_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1410286302&sr=1-2

http://www.amazon.com/Faith-Instinct-Religion-Evolved-Endures/dp/0143118196/ref=la_B001H6WF40_1_3?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1410286302&sr=1-3

http://www.amazon.com/Troublesome-Inheritance-Genes-Human-History/dp/1594204462/ref=la_B001H6WF40_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1410286302&sr=1-1

It is pagan, you should read a book on it:

The Gnostic Origins of Roman Catholicism https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00GDFVN34/ref=cm_sw_r_other_apa_i_CYDSDbQYT3PJ7

The Faith Instinct: How Religion Evolved and Why It Endures. Nicholas Wade. 2010

We must have different ones... this is the one I'm reading https://www.amazon.com/Ethics-Dietrich-Bonhoeffer-Works-Vol/dp/0800683269/ref=sr_1_3?ie=UTF8&qid=1491171237&sr=8-3&keywords=bonhoeffer+ethics

A Fortean scholar testing the limits of the impossible.

If you like Frederic Myers, check out Authors of the Impossible.

>Kripal grounds his study in the work of four major figures in the history of paranormal research: psychical researcher Frederic Myers; writer and humorist Charles Fort; astronomer, computer scientist, and ufologist Jacques Vallee; and philosopher and sociologist Bertrand Méheust.

(edit: here's the paperback link http://www.amazon.com/Authors-Impossible-Paranormal-Jeffrey-Kripal/dp/0226453871/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&sr=&qid=)

If you think you might want to go after some of the original stories, Bullfinch's Mythology is a really classic collection of myths, and of course there's Grimm's Fairy Tales and Aesop's Fables. Richard Burton's translation of The Arabian Nights is the English language classic there, The Tale of the Genji is something similar from Japan.

You might also like some related nonfiction, like The Golden Bough which is about the origins of myth and religion, The Hero With a Thousand Faces about the similarities across various stories of heroes, and more recently, The First Fossil Hunters which looks at how finding elephant and dinosaur bones may have inspired some of the Greek monsters like cyclops and griffin.

This is a good one, too. Also, a little more recent.

http://www.amazon.com/Orientalism-Religion-Post-Colonial-Theory-Mystic/dp/0415202582/ref=sr_1_21?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1324783868&sr=1-21

We have to be very careful here, conceptually. You're potentially right in saying that many tribes have never developed anything like religion. The 'potentially' is based in what you consider 'religion'.

A huge amount of my undergrad and grad-level work in religious studies involved field work among the Mi'kmaq (the First Nations tribe of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in eastern Canada). Traditional Mi'kmaq beliefs don't match what most Euro-Americans consider 'religion'. There are no dogmatic teachings; no holy scriptures; no popes or hierarchy; no concept of sin or divine commandments, and so forth. In fact, most of the world's religions developed without scriptures, popes, concepts of sin and so on. Richard King's Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and the 'Mystic East' and Mallory Nye's Religion: The Basics are both fantastic in exploring these ideas and, IMO, absolutely essential reading for anyone who wishes to engage in high-level academic discussions on religion (be they pro-, con- or neutral).

To anyone employing the Euro-American religious paradigm as an interpretive framework, the Mi'kmaq appear to have no religion at all (until Catholicism came along with the missionaries anyway). This isn't correct, however. The Mi'kmaq way of life is heavily spiritualized, to the point where there is no division between 'secular' and 'religious'. It's all just 'Life'. We might say that Mi'kmaq religion is based on living well. Indeed, the entire religio-spiritual outlook of this people is based in concepts of interconnectedness between all things. Ecology, essentially. This is not to say that it is purely rational (using that term in the scientific sense)...there is a belief in spirits, and also a very well-developed system of medicine that treats physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual afflictions differently (and successfully!).

Religion (and by that word I mean religious beliefs and practices, not religious institutions) is very much a quest for meaning and understanding, and often arises from the mythologizing of traditional lore and so forth.

I would contend that any group that possesses ritualized taboos, myths, and an inherited tradition (written or oral) has, at its heart, religion (or spirituality, if 'religion' rankles you too much).

If you can present an example of a tribe with absolutely none of this, I would be very interested in finding out who they are (and I say this not out of hostility, but rather genuine interest...the study of religion is my field!).

EDIT: "First Nations" is Canadian for 'Native Americans'.