Top products from r/askastronomy

We found 43 product mentions on r/askastronomy. We ranked the 94 resulting products by number of redditors who mentioned them. Here are the top 20.

1. An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics (2nd Edition)

Sentiment score: 2

Number of reviews: 5

Used Book in Good Condition

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews2. NightWatch: A Practical Guide to Viewing the Universe

Sentiment score: 3

Number of reviews: 4

Used Book in Good Condition

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews3. Turn Left at Orion: Hundreds of Night Sky Objects to See in a Home Telescope - and How to Find Them

Sentiment score: 3

Number of reviews: 3

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews4. Celestron - SkyMaster Giant 15x70 Binoculars - Top Rated Astronomy Binoculars - Binoculars for Stargazing and Long Distance Viewing - Includes Tripod Adapter and Case

Sentiment score: 2

Number of reviews: 3

Multi coated opticsLarge aperture perfect for low light conditions and stargazingTripod adapter 13 millimeter (0.51 inch) long eye relief ideal for eyeglass wearers; Linear Field of View (@1000 yards) / @1000 meter) 231 feet (77 meter)Diopter adjustment for fine focusing; Angular field of view 4.4...

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews5. Fundamentals of Astrodynamics (Dover Books on Aeronautical Engineering)

Sentiment score: 0

Number of reviews: 2

Dover Publications

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews6. Chasing Venus: The Race to Measure the Heavens

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 2

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews7. Sky & Telescope's Pocket Sky Atlas

Sentiment score: 2

Number of reviews: 2

Used Book in Good Condition

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews8. Celestron - Cometron 7x50 Bincoulars - Beginner Astronomy Binoculars - Large 50mm Objective Lenses - Wide Field of View 7x Magnification

Sentiment score: 3

Number of reviews: 2

Wide field of view reveals a larger portion of the night sky, allowing you to view more of the comet's impressive tailLarge 50 mm objective lenses have tremendous light gathering ability, ideal for astronomical useMulti coated optics dramatically increase light transmission for brighter images with ...

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews9. Orion 8945 SkyQuest XT8 Classic Dobsonian Telescope

Sentiment score: 2

Number of reviews: 2

Item may ship in more than one box and may arrive separatelyA large aperture Classic Dobsonian reflector telescope at a very affordable price!8" diameter reflector optics lets you view the Moon and planets in close up detail, and has enough light grasp to pull in pleasing views of faint nebulas, gal...

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews11. SVBONY Telescope Eyepiece Fully Mutil Coated 1.25 inches Telescope Accessories Set 66 Degree Ultra Wide Angle HD 6mm for Astronomy Telescope

Sentiment score: 0

Number of reviews: 1

Fully multi coated broadband green optics with superior optical performance;clarity is great and the magnification is truly represented66 degree AFOV perfects for broad field lunar observations;medium sized star clusters;wide range of cloudy nebulas and deep sky targets with extra sharpnessMulti gro...

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews13. The Observer's Sky Atlas: With 50 Star Charts Covering the Entire Sky

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Springer

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews16. Atom: A Single Oxygen Atom's Journey from the Big Bang to Life on Earth...and Beyond

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

ISBN13: 9780316183093Condition: NewNotes: BRAND NEW FROM PUBLISHER! 100% Satisfaction Guarantee. Tracking provided on most orders. Buy with Confidence! Millions of books sold!

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews17. Chasing Venus: The Race to Measure the Heavens

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

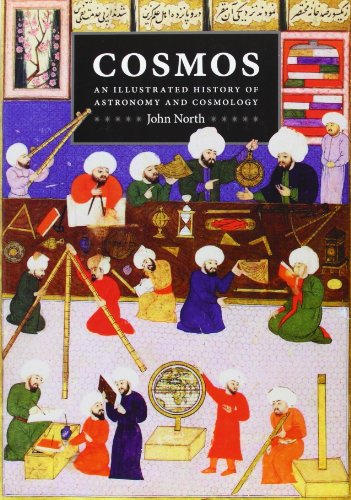

Show Reddit reviews18. Cosmos: An Illustrated History of Astronomy and Cosmology

Sentiment score: 0

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews

I would say that the best thing that you can probably do is to join a local astronomy club. They're more than likely going to have "star parties" where they all bring different telescopes and look at different things in the night sky. It should give you a good taste of what you can see, the pros and cons of different telescopes, and real world experience. You're also going to have a ton of experienced observers who you can ask questions and talk with.

Besides that, I would probably pick up a book called Turn Left at Orion and a star atlas (my personal favorite is Sky and telescope Pocket Sky Atlas). Turn Left at Orion is essentially a beginners guide to amateur astronomy. It tells you what the best things to observe are during different times of the year, descriptions of them, how to find them, and other things. A star atlas is essentially a map of the night sky. I would also look into Stellarium. It's a free program that shows you what your night sky looks like based on your date, time, and where you live. It's pretty much an interactive star atlas. Also, if you have any book money left over, you might consider getting RASC's 2017 Observer's Hand. It tells you, in detail, what important things are going to be going on above our heads in 2017. It also has some nice articles for beginning astronomers, a bunch of nice maps, and a lot of helpful charts. I wouldn't call it a necessity, but it's really nice to have.

I would also recommend joining an online astronomy forum. Cloudy Nights is my favorite. The folks there are all passionate about astronomy, very nice, and very knowledgeable.

Lastly, and this is the most important piece of advice I can give, is to just get out there and start observing. You don't need a telescope or even binoculars. Go out and try to find constellations or try to find where the planets currently are or see if you can see some of the brighter Deep Sky Objects (those are essentially anything that isn't a planet or the moon). The Pleiades and the Orion Nebula are great first things to look for, for instance. Just enjoy being out there under the stars. It's a great feeling.

Clear Skies!

This is a long answer, but you need to know a bit of the history of astronomy to understand how astronomers figured out how to calculate the distances to stars. Astronomy is the oldest science there is. It goes back to the most ancient civilizations, the Messpotamians were looking up at the sky and studying it. Even they noticed that the stars were not all there was. The stars themselves, sure, lots and lots of dots. But there are also 5 planets, the sun and the moon and all of those things move across the sky as time passes. The stars all moved together, but the planets were different. They didn't follow the same path across the sky as the stars did.

Ancient thinkers like Aristarchus and Eratosthenes calculated surprisingly accurately the circumference of the earth and the scale between the earth, the moon and the sun. The used measurements from lunar and solar eclipses, geometry, etc to make really, really good estimates for the time.

In the 1400's or so, attempts to understand what we saw in the sky were made by people like Johannes Kepler. He saw the sky as layers of geometric shapes or crystal like... things, that rotated around the earth. A model he build looked like this with earth in the center, the sun above it, the moon above that, mars above that and so on until you got to the stars which was the biggest enclosure. He tried for many years to figure out why mars retrograded, that it appeared to stop, move backwards, stop, then move forwards again over time in the sky. He eventually figured out that it was because the planets didn't move in perfect circles like people thought, but that they moved in elipses or ovals

Nicolaus Copernicus was one of the first to propose that the earth revolved around the sun, and not the other way around, using what Kepler figured out which was that the planets do not move in circles, but elipses (ovals).

Galileo Galelie with an understanding of Keplers and Copernicus' work was the first person to point a telescope (invented a few years earlier by someone else) at Jupiter in the sky. He discovered that Jupiter had 4 moons that orbited around it and he could observe and measure it. This was further proof that the earth went around the sun and not the other way around.

There are also sometimes rare events, which give us invaluable information used to calculate astronomical distances. One such event being a transit. That's when one of the planets close to the sun, Mercury or Venus, passes in front of the sun from earths point of view. Here it is in 2012 Astronomers could use this information to calculate the distances to the planets, and determine the size of the solar system. In 1761 and 1769 Hundreds of scientists from all across the world planned for the transit. Some traveled half way across the world, not an easy feat in the 1700's to get the data. Then they all collaborated it (which took years) and this gave us a much better understanding of the size of the solar system and the distances involved.

In the late 1700's William Herschel and Charles Messier were cataloguing stars and nebula. It turns out that what looks like just dots with the naked eye have a lot of differences when viewed through a telescope. Some are brighter, some dimmer, some are bigger, some are smaller and even some of different colors. Many stars will also fluctuate in how bright or dim they are over time, like a very slow pulse. It also turned out there were objects that weren't stars in the sky. But they were too dim to see with the naked eye and only visible in a telescope. Messier cataloged over 100 galaxies and nebula and produced a guide still used today. The telescope also enabled astronomers to figure out that there weren't about 5000 or so stars that we could see with the naked eye, as everyone in history before then thought, but that there were millions upon millions (and as telescopes got better, billions upon billions) of other stars, too dim to see with the naked eye. All this can be measured, recorded, compared and calculated. The invention of the telescope gave astronomers lots and lots (and lots and lots) of data to work with.

Here's where we get to the specific of your question.

In the late 1800's Henrietta Leavitt employed as a "computer" (someone who just "computes", or records, analyses and does the math of data collected about stars) discovered the relation between the luminosity and the period of Cepheid variable stars. She figured out how to determine the distance to astronomical objects. First calculating the Large & Small Magellanic Cloud, two small galaxies outside that were thought to be just clouds of dust.

Edwin Hubble, namesake of the Hubble Telescope used Leavitt's data and method to figure out that the universe was expanding, by measuring the redshift of galaxies outside our own. This was the biggest step towards the big bang model of the universe.

These are only really the top names and discoveries. Many scientists during all that, and up until now have worked together to figure out how to determine the size of a star, what the stars are made of, how they work and what they actually are, and how to figure out how far apart all those little dots are.

But what we know about the universe today is everything learned in many fields across lots and lots of time. If you're really interested in a great "history of science, what we know and how we know it" I'd recommend A Short History Of Nearly Everthing by Bill Bryson. It does a great job of explaining all this and more in easy to understand laymen terms.

Hello :-)

Is it the Celestron Cometron or Powerseeker 114AZ?

The Cometron 114az is a short reflector with a short 450mm focal length. It has a parabolic mirror, so it's OK, but not great at high magnification (large obstruction, coma, parabolization quality...). The mount stability should be OK.

The Powerseeker 114az is a long reflector, the ~F/8 aperture ratio has benefits (easy to reach higher magnification, small obstruction, parabolization is no issue). It will already show a lot! :-) The problem is the mount, it's not good for such a big telescope. You can build a simple "rockerbox" to turn it into a dobsonian (1 2).

If it's another Celestron, the short 114 with 1000mm focal length, it's a "bird-jones" with flawed optics. It will still show the moon nicely, glimpses of the planets and some DSO ... But has contrast & collimation issues.

All basic sets have one thing in common: The kit eyepieces aren't great. Don't buy an eyepiece-kit though! :-)

What to expect in differtent telescope aperture sizes.

If you are on a budget, you can get the Celestron Cometron 7x50 for under $30. Usually you get what you pay for, but they aren't too bad. 1 2. Under less ideal conditions (light pollution) 10x50 might be better (smaller exit pupil), but personally, I find 10x already difficult to hold steady when observing faint nebulae over a longer period of time. If you want something better, you can easily spend 100 or 200 dollars on some binoculars.

TL;DR: What telescope exactly?

? ? :-) ! ! Clear skies!

Nice! Well, I would definitely recommend he read some Carl Sagan (Cosmos and Pale Blue Dot) and Steven Hawking (Brief History of Time, The Grand Design, etc.). Looks like there's a really good book out since 3 days ago called, The Science of Interstellar by Kip Thorne. This would be a really good book to get him. I picked up a pretty old Astronomy textbook a while ago for a really cheap price that I'm going to look over a bit, but I don't know of any specific ones to recommend. Here's an awesome PDF I got from a redditor who was offering an eBook and PDF of his book for free to anyone who asked: http://docdroid.net/kyjz

You can't go wrong with a Dobsonian in the 6"-8"-10" range. At the lower end they'll be less expensive and more portable, but at the higher end you'll be able to see more.

http://www.telescope.com/Telescopes/Dobsonian-Telescopes/Classic-Dobsonians/pc/1/c/12/13.uts

I have an Orion 8" Dobsonian. They also sell Intelliscope models that will assist you in finding objects. I like finding things on my own, by star-hopping, but it takes a little patience and experience. These books will help:

http://www.amazon.com/Turn-Left-Orion-Hundreds-Telescope/dp/0521153972

http://www.amazon.com/NightWatch-Practical-Guide-Viewing-Universe/dp/155407147X

I recommend getting one with at least two eyepieces, or at least one eyepiece and a Barlow, so you'll have a choice of magnifications.

And whether or not you get a telescope, a pair of binoculars is a good thing to have. 7x50s are nice and easy to use without a tripod. 10x50s will show you a little more but are a little harder to hold steady. Anything larger and you'll probably want a tripod for them. I have 10x50s and am considering getting these:

http://www.amazon.com/Celestron-SkyMaster-Binoculars-Tripod-Adapter/dp/B00008Y0VN

I also got my first telescope when I was 11. The best thing to do to get into the hobby is going to your local amateur astronomers group and start observing with them. They will know what object you can see, and you will learn a lot from their experience. I started like that and a few years later build my own telescope (with the help of one of the members of the astronomers group).

I would also recommend not to use the "go-to" function on the telescope if it has one, so that you learn to know the sky and to search by yourself (it's a really good feeling when you finally find the object you're looking for).

A really great book I use almost every time I get my telescope out is the Observer's Sky Atlas written by Erich Karkoschka (http://www.amazon.com/Observers-Sky-Atlas-Charts-Covering/dp/0387485376/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1418284218&sr=8-1&keywords=the+observer%27s+sky+atlas)

In his promos for Space Chronicles, Tyson likes to call space enthusiasts delusional. I agree with him that Apollo was a cold war fluke.

But his approach is nothing new either. Space enthusiasts have been arguing investing in space exploration boosts STEM and the economy. For decades. Has Neil's 2012 book changed the minds of policy makers? I don't see any indication Hillary, Bernie or Trump has taken any interest in Tyson's arguments.

In short, Tyson is just as delusional as the rest of us space enthusiasts. We'll be lucky if NASA continues getting 15 to 20 billion per year.

The only possibility I see for a change in paradigm is commercial space making money. If space resources give a return on investment, our expansion into space will follow naturally.

Here are a few books on possible space resources/settlement:

Mining The Sky by Dr. John S. Lewis

Asteroid Mining 101 by Dr. John S. Lewis

Rain of Iron and Ice by Dr. John S. Lewis

Dr. Lewis was a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona. Rain of Iron and Ice is about possible meteorite impacts. The other two books explore the possibility of mining asteroids.

Moon Rush by Dennis Wingo

Wingo advocates mining the moon for platinum and rare earth metals. A very long shot, in my opinion. However the first chapters describe how government-private partnerships built U.S. transportation and communication infrastructure. I believe Wingo is correct that it'd take such a partnership to establish infrastructure in the earth moon neighborhood.

The Value of The Moon by Paul Spudis

Spudis believes there are rich water ice and other volatile deposits in the lunar cold traps. These crater floors that haven't felt sunlight in eons are as cold as 30 K. These pits of eternal night neighbor plateaus of eternal light. The polar plateaus receive nearly constant sunlight and thus don't suffer the two week days and two week nights of lower lunar latitudes. Temperature swings are much milder.

Spudis advocates mining lunar water and exporting lunar propellent throughout the earth moon neighborhood.

Your teenaged relative could learn how to navigate the stars, and identify constellation locations by sight with a quality pair of binoculars and a book like Turn Left at Orion.

For an even more involved and rewarding gift, check out local telescope making workshops.

You only need a mirror blank (typically made of pyrex glass) and some grit, so he can certainly do this at home when he's not at the workshop. An 8" mirror will take about 40 hours of grinding and polishing the surface, which ends up being optically superior to machine-made mirrors.

If you feel like reading on your own, over at /r/astrophotography we have a pretty comprehensive Wiki geared toward helping you figure out which scope works for you. Keep in mind though it's with imaging in mind and not just basic observing.

Orion is a quality manufacturer, their gear is used pretty widely across the board with amateurs and enthusiasts for observation and astrophotography.

The first thing you need to do is have real expectations, all the cool space shots you see are always done with long exposures, usually stacked. This means that your camera sensor is opened up to accept a a lot of photons over a longer period of time, the resulting image ends up in way more detail and contrast than you would get with just viewing through the eyepiece. If you scroll down toward the bottom of this you'll see some comparisons of what you can expect to see.

If you don't plan on imaging, you essentially want the largest aperture scope you can afford, this will be a reflector like the one you linked. However I would look for a Dobsonian mount instead of a equatorial (tripod mount). You can get an 8" Reflector for just about $400. But this is a big footprint scope, heavier and not totally easy to tote around frequently. This is kind of a catch-22 because the way you will get the most out of this scope is to bring it to the darkest area possible, up into the mountains like you mentioned would be ideal.

A couple good examples would be either M31 (Andromeda) or M42 (Orion Nebula) both large and fairly distinct objects, M42 is actually the closest Nebula to us and that's one of the reasons it's so widely photographed and viewed. Andromeda with a 8' Reflector at a dark site would yield you something like this. On the other hand, an image from user /u/kindark with a less powerful scope but multiple stacked exposures was able to produce this. The former is more what you can expect to actually see.

The most common introductory book to astronomy is probably this one:

https://www.amazon.com/Introduction-Modern-Astrophysics-2nd/dp/0805304029

It is pretty much the bible of undergraduate astronomy. Keep in mind, that a lot of it is going to be hard to follow if you do not have a couple of semesters of calculus and physics under your belt, but if you want an overview of the material you would be learning as an undergraduate. It is pretty thorough, though a bit outdated at this point.

There are also plenty of textbooks used to teach GE astronomy classes that do not have a steep math and physics assumption. You might want to find out what the local college or university uses for their GE astronomy classes and start there. Those books should be easier to follow.

The Cosmic Perspective is a pretty good introductory text for astronomy.

The most comprehensive text in astrophysics is An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics by Carroll and Ostlie (often referred to as the "big orange book," or BOB for short). This text is much more mathematically involved, but will teach you most anything you might want to know about astrophysics.

If you really want to understand astronomy, then BOB is the way to go, but you'll have to learn calculus and a couple of years of physics to understand some of the concepts. I would suggest starting with The Cosmic Perspective and learning some physics and math if you become interested enough to move on to BOB.

I'm not familiar with the book you mentioned, but the best one I know for people getting into astronomy is NightWatch by Terence Dickinson.

I also enjoyed this one: Link

It's not overwhelming and does a good job of explaining the basics.

A good place to start is Introduction to Modern Astrophysics, by Carroll and Ostlie:

https://www.amazon.com/Introduction-Modern-Astrophysics-2nd/dp/0805304029

It's a good upper-undergrad to grad-level textbook that covers a lot of topics.

I can indeed. I did the experiment myself a few months ago as a part of my course so I have the activity handbook. I'll go back and read it again tomorrow my time to refresh my memory and post some details at some point tomorrow. If you don't have one, try to get a star atlas. Stellarium is useful but I find using a book easier.

I use this one:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Sky-Telescopes-Pocket-Atlas/dp/1931559317/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1520534912&sr=8-2&keywords=pocket+star+atlas

Will post details of the experiment tomorrow. Am just going out for dinner.

I've owned about a dozen telescopes and the best beginner telescope is by far the Orion skyquest, 8 inch. You can find them used on craigslist for half the price. https://www.amazon.com/Orion-8945-SkyQuest-Dobsonian-Telescope/dp/B001DDW9V6/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1491667181&sr=8-1&keywords=orion+skyquest+xt8

Thank you! I passed the link on to my parents, and I am considering getting him this book as well.

This, but here is a much better purchase

You want these. This is such a ridiculously good deal--these should cost at least $200.

http://www.amazon.com/Celestron-SkyMaster-Binoculars-Tripod-Adapter/dp/B00008Y0VN/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1453001226&sr=8-1&keywords=skymaster

ya your telescope will take any 1.25" eyepeice.

https://www.amazon.com/SVBONY-Telescope-Eyepiece-Accessories-Astronomy/dp/B07JWDFMZ4/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=6mm+svbony&qid=1570632198&sr=8-1

Carrol and Ostlie, a.k.a BOB (big orange book).

Maybe Fundamentals of Astrodynamics

Fundamentals of Astrodynamics (ISBN-13: 978-0-486-60061-1) seems to cover the basics.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Astronomy-Dummies-Stephen-P-Maran/dp/1118376978

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Space-Exploration-Dummies-Cynthia-Phillips/dp/0470445734

I can only suggest those two.

I was always partial to Astronomy Today. You can find older editions for significantly cheaper, although you'll get outdated information about Pluto and exoplanet discoveries.

You could write up on the history of the Transit of Venus. It was a huge event in 2012, and will not happen again for 117 years or something like that. The book Chasing Venus outlines the history of the event, what early astronomers had to go through to measure it (like travel half way around the world, only to miss the event because of clouds, then return home to find out he was declared dead and all his possessions sold off.) The story is fascinating, but so is the hard data. The measurements of the transit enabled astronomers to calculate the distance to the sun.

The Georgian Star by Michael Lemonick. Although it focuses on the lives of William and Caroline Herschel, it is an interesting and easily digestible story of a particular time in the history of astronomy.

[Cosmos: An Illustrated History of Astronomy and Cosmology] (http://www.amazon.com/Cosmos-Illustrated-History-Astronomy-Cosmology/dp/0226594416/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1452133510&sr=8-1&keywords=cosmology+john+north) by John North. I bought this on a whim. It is very informative, but parts of the text have overwhelmed me because of my ignorance of subjects such as trigonometry and calculus.

Start here and go through the trig and calculus videos, problems, etc. Then hit up the physics stuff. After that you might want to find other resources to learn Trig, Calc, and College level physics. Then you can think about picking up this hefty thing.

Edit: There is also an "ebook" version of the book above. I won't say where. But it's out there.