(Part 2) Top products from r/communism101

We found 20 product mentions on r/communism101. We ranked the 148 resulting products by number of redditors who mentioned them. Here are the products ranked 21-40. You can also go back to the previous section.

21. Khrushchev Lied: The Evidence That Every Revelation of Stalin's (and Beria's) Crimes in Nikita Khrushchev's Infamous Secret Speech to the 20th Party ... is Provably False by Grover Furr (2011-05-03)

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

426 pp. Paperback edition.

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews22. NYNELSONG Mouth Shield Seamless Pattern Tea Coffee Dishes Tea Coffee d Face Shield

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Very soft, durable and breathable.It is perfect for everyday use.Elastic earloop, covering the face from nose to chin. Full coverage.Washable and reusable.Minimum amount you need we recommend is 3 pieces for easy changing.Suitable for cycling, bus, metro, other public places, etc all outdoor activit...

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews23. Hegel: A Very Short Introduction

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Oxford University Press USA

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews24. Music in the Late Twentieth Century: The Oxford History of Western Music

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Oxford University Press USA

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews25. Soviet Cinema in the Silent Era, 1918–1935 (Texas Film Studies Series)

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews26. Hunger and Public Action (Wider Studies in Development Economics)

Sentiment score: -1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews27. The Enigma of Capital: and the Crises of Capitalism

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews28. The Cold War: A Global History with Documents (2nd Edition)

Sentiment score: 0

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews29. Economic Development in East-Central Europe in the 19th and 20th Centuries

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews30. A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882-1930

Sentiment score: -1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews31. The Cinema of the Soviet Thaw: Space, Materiality, Movement

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews32. Contending Economic Theories: Neoclassical, Keynesian, and Marxian (The MIT Press)

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

MIT Press MA

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews33. Body and the East: From the 1960s to the Present

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews34. Lenin for Beginners (Pantheon Documentary Comic Book)

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews35. Offspring of Empire: The Koch'ang Kims and the Colonial Origins of Korean Capitalism, 1876-1945 (Korean Studies of the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies)

Sentiment score: -1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews36. The Life and Thought of Friedrich Engels: A Reinterpretation

Sentiment score: -1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews37. Life and Terror in Stalin's Russia, 1934-1941

Sentiment score: -1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews38. The Road to Terror: Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939 (Annals of Communism Series)

Sentiment score: 0

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews

>My question is, does something like this exist for marxist economics?

It's a solid question. One I'm actually trying to flesh out myself. I don't trust myself to give a good enough explanation of the topic so rather than that I'll try to point you in a couple directions.

Before I start listing stuff off though I'm going to make a quick note on the nature of the problem. In my opinion, one major feature of Marxian economics which has left it so fractured is the fact that Marx never got around to writing a tract on methodology. Because we have to reconstruct his method based on how he used it, it leaves a lot of room for debate over the nuances of what Marx was and wasn't doing. In broad strokes you can identify the major component parts, but once you get into the nuts and bolts of how each fits together, it can be tough to handle. I've found Paul Paolucci's book, 'Marx's Scientific Dialectics' to be useful on this front, but I'm not an expert and because of that remain skeptical even of that book as I recommend it.

I'd also note that I think it is more useful to categorize Marxian economics under the rubric of Political Economy rather than Economics as it's practiced today.

[This list is by no means exhaustive] Anyway, some books/articles/resources you may find helpful:

The Marxists Internet Archive Encyclopedia - Useful in general, may not help on this specific question.

Contending Economic Theories: Neoclassical, Keynesian, and Marxian by Wolff and Resnick - Generally a useful text/primer. I'd suggest checking the table of contents provided there to see if it will address some issues you're interested in. I think the discussion of 'Class' is pretty useful.

'Microfoundations of Marxism' by Daniel Little - This article appears as chapter 31 in a text entitled Readings in the Philosophy of Social Science

'The Scientific Marx' by Daniel Little - I haven't been able to read this yet but chapter 5 is devoted to Microfoundations and chapter 6 to the use of evidence.

'Analytical Foundations of Marxian Economic Theory' by John Roemer - Roemer is(was?) a member of the analytical Marxist tradition which sprang up in the 1970s. One of their major differences between other forms of Marxism was the rejection of dialectics and the use of Neoclassical modelling tools to develop various Marxian economic/social theories. Many of their methods and developments are considered controversial among orthodox Marxists, but I think they're worth reading none-the-less. This leads naturally to:

Analytical Marxism by John Roemer - A more general take on analytical Marxism. Addresses issues with historical materialism, combining Marxism with game-theory and even moral considerations.

I've also been reading the Elgar Companion to Marxian Economics which contains a set of essays on various topics within more orthodox Marxian econ

We censored art too, and for less good reasons. Have your friend go to cia.gov and read about the "Congress for Cultural Freedom." This was a CIA-backed organization that actively promoted avant-garde art as a cold war measure; Jackson Pollock, the famous "abstract expressionist" who literally just threw paint at canvases, was the one of the artists they funded.

Now you might argue that promoting certain kinds of art is different than censoring anything that isn't in the Official Style. But Western artists were under heavy pressure to toe the avant-garde line. McCarthyism, for example, all but forced American composers to write serial music: a heavily mathematized form of composition that was mostly discouraged in the Soviet Union. Music written in more traditional styles became branded as "communist." In Europe, the American-backed Darmstadt Summer School -- which, until very recently, one had to attend in order to be recognized as a composer in the West -- basically condemned anything but the most avant-garde styles as "authoritarian." Aaron Copland, a leftist American composer whose work often drew from folk styles, went from this to this after being called in front of the House Un-American Activities Commission.

Which is to say: art is not apolitical, and it does not take place in a vacuum. From the standpoint of their class interests, the western bourgeoisie were perfectly correct in censoring art that, from their standpoint, was subversive. Similarly, the socialist countries were and are perfectly justified in censoring art that is being used as a wedge to to drive their societies apart. Interestingly, socialist countries' bans on avant-gard artistic styles were never as complete as the Western media likes to claim: in addition to very traditional pieces like Gliere's Heroic March for the Buryat-Mongolian ASSR you had things as modern as Penderecki's Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima . This actually seems to argue for a greater artistic plurarity than you had in the West; the criteria was not whether art was old or new, but whether it advanced or retarded the socialist cause.

Sources:CIA article on the Congress for Cultural Freedom

Richard Taruskin: Music in the Late 20th Century

I'm no expert but I'll answer your questions as best as I can.

Of course I second Hobsbawm 1789-1914 series (not a fan of age of "Age of Extremes" liberal narrative though -- Hobsbawm was right, he wasn't capable of writing a history for that era).

I haven't read them but Ivan Berend and Georgy Ranki are two historians I have on my "to read someday" list that extensively cover that era. Specifically they wrote "Economic Development in East-Central Europe in the 19th and 20th Centuries" and "Hungary: a Century of Economic Development" together. It looks like Berend might've become somewhat anticommunist after the the collapse of socialism in Eastern Europe but he also produced another history book on the era which Hobsbawm seemed to review positively. Anyway, Berend seems to have been strongly influenced by Marxist historiography and to cover what Hobsbawm covers as well only focusing more on the region you're likely interested in.

I unfortunately don't have pdfs but the first two works I mentioned can be purchased used for fairly cheap, you might try abebooks.

/u/ksan recently wrote a good piece that lists a number of introductory texts for Hegel here. I'm currently in the middle of reading Beiser's Hegel and it's very manageable. If you want something lighter, I'd recommend starting with this first but it is a very short introduction. Whilst it's a hundred pages or so you'll be left feeling like you just read an abstract. You should be able to find a copy of both texts online in PDF form without any trouble.

At the very least, you'll probably want to get a grasp of what the structure of

PhenomenologyPoR is and what Hegel is trying to convey before Marx's Contribution will make any sense.Although it is usually ignored in these kind of conversations, performance art is very interesting to think about within the context of soviet rule. There is an interesting book, Body and the East: From the 1960s to the Present by Zdenka Badovinac. I might be able to send you a free copy on Google Drive or something. There is also Antipolitics in Central European Art: Reticence as Dissidence under Post-Totalitarian Rule 1956-1989 and Art and Democracy in Post-Communist Europe.

Of course, there is a problem with speaking about performance art within a marxist context. Performance Art is postmodern, while traditional Marxist ideology is modern. Still, I hope this is still a valid post. Here is a small fragment I'll just copy paste from an essay I wrote on Performance Art which might help you understand how it influenced a change in post-communist societies.

>‘Performance’ or ‘body’ art has reframed the notion of art in fundamental ways, and has played an essential role in the shift from modernism to postmodernism. The shift, according to Amelia Jones, is caused by the dislocation of the modernist Cartesian subject through the implementation of the body and its performance into the artwork (Body Art, 1998). In other words, unlike traditional art, there is no dualism concerning the artist and the artwork, but rather the artist’s biological existence becomes part of the artwork. Much like other postmodern elements, it is counter-formalist. The performative body of the artist breaks down the hierarchies between actor, spectacle and spectator that are inherent in traditional forms of art. The meaning of body art cannot be defined as a certain or fixed object, it is open-ended and indefinite, and thus destabilises structures and assumptions of formalist art history and criticism. This destabilisation also happens through the use of the body, as racial, ethnic and sexual identity of non-normative artists naturally challenge not only conventional art itself, but how the spectator looks at, studies and evaluates art too (Jones, 1998). The prime of performative art was in the East, as the inherently anti-authoritarian art was used to battle an authoritarian government. Performative art in the East rose to challenge western values and notions. The second wave feminist movement and the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s and 70s introduced the term ‘Body Politics’ and the phrase ‘the body is political’, a theory that many body artists adopted and expressed with their performance, notably Carolee Schneemann’s Interior Scroll.

Well you'll have to pick one is the point. You can either pick a type of culture or a specific period of time, because all culture ussr too broad as to be meaningless. I find cinema the most interesting and you'll have to read about early Soviet cinema (the Eisenstein-Vertov debate is the foundation of cinema), then the realist file and melodramas of the 30s and early 40s, then the height of modernist epics vs "bard" films in the 60s-70s, then science fiction and petty-bourgeois "gore" films of the 80s. There is a lot of overlap between these categories and periods and many of these categorizations come from western academia rather than the films or Russian people (hence tinged with anti-communism) but you still want to think about films historically and what they mean as historical objects vis-a-vis socialism's rise and fall in the USSR. Also be careful what you read because "good" is defined as "anti-communist", that is so foundational it isn't even mentioned. The essential thing is to start at the beginning so you understand what film is, what its class nature and social function are, what are its technical possibilities (in a McCluhanian sense), and what its relationship to history is. Avoid wikipedia for anything other than basic information obviously.

E: there's not much point recommending books since you'll read whatever the school library has but you'll want to start with a basic reader like this

https://www.amazon.com/Russian-Soviet-Cinema-Guide/dp/0810876191/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1540054345&sr=8-1&keywords=Soviet+cinema

And then specific investigations like these

https://www.amazon.com/Cinema-Soviet-Thaw-Materiality-Movement/dp/0253026962/ref=sr_1_3?ie=UTF8&qid=1540054345&sr=8-3&keywords=Soviet+cinema

https://www.amazon.com/Russian-Science-Fiction-Literature-Cinema/dp/1618117238/ref=sr_1_4?ie=UTF8&qid=1540054345&sr=8-4&keywords=Soviet+cinema

https://www.amazon.com/Soviet-Cinema-Silent-1918-1935-Studies/dp/0292776454/ref=sr_1_8?ie=UTF8&qid=1540054345&sr=8-8&keywords=Soviet+cinema

And throw in a film theory reader

https://www.amazon.com/Film-Theory-Basics-Kevin-McDonald/dp/1138797340/ref=sr_1_fkmr3_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1540055087&sr=8-2-fkmr3&keywords=Film+theory+vertov+eisenstein

https://www.amazon.com/Understanding-Film-Perspectives-Mike-Wayne-ebook/dp/B00V50U6SA/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1540055250&sr=8-2&keywords=Marxist+theories+of+film

Personally I didn't like the latter but I understand it is not for me.

People believed in a human nature based on God and the Divine Right, or some variation of those beliefs outside of the European feudal system. In Europe at least, profit-making was actually shunned for a long time, often based on "Christian values", before capitalism became a popular idea, let alone a mode of production. This video expands on that a bit, but is also a good video to watch concerning the beginnings of capitalism in general.

I would also check out Political Economy by John Eaton and The Worldly Philosophers by Robert Heilbroner

I've heard really good things about Heinrich's Introduction to the First Three Volumes of Karl Marx's Capital. I just picked it up the other day, but I haven't read it quite yet.

Otherwise, you should check out the link to David Harvey's video series (found in the sidebar). Or, for a contemporary application of Marx's theories, Harvey's Enigma of Capital is a worthwhile read.

Marx for Beginners and Lenin for Beginners are decent books.

Trường Chinh's August Revolution and The Resistance Will Win are amazing.

This is the feminist reading list I usually trot out when someone asks for recommendations. I've starred the ones that would probably be most useful to you.

Edit: and in no particular order

Feminism is for Everybody, bell hooks*

Politics of Reality, Marilyn Frye

Feminist Theory, From Margin to Center, bell hooks

Ain't I a Woman, bell hooks

The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir

Borderlands/La Frontera, Gloria Anzaldua

Nickel and Dimed, Barbara Ehrenreich*

Sister Outsider, Audre Lorde

Men Explain Things to Me, Rebecca Solnit

The Feminine Mystique, Betty Fridan

Women, Race, and Class by Angela Davis*

Gender Trouble, Judith Butler

Capitalism, a Ghost Story, Arundhati Roy*

Sex and Social Justice, Martha Nussbaum

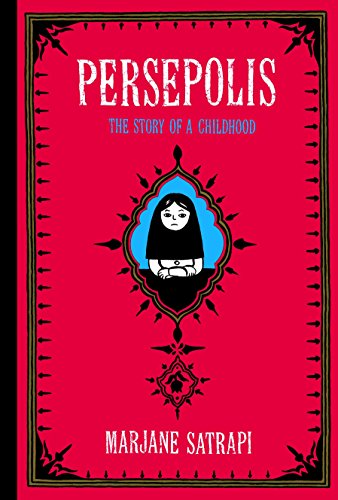

Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi

We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Snow Flower and the Secret Fan by Lisa See

The Color Purple by Alice Walker

This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color

The New Gender Workbook by Kate Bornstein

Whipping Girl by Julia Serrano

Believe it or not, my Cold War history class this past semester used this textbook, and it went in depth about the Viet Minh as well as other similar revolutions: The Cold War

I've read parts of this and several people here have recommended Getty's books.

I'll just say don't overthink petit-bourgeois delusions and resentments if you're interesting in drawing real lessons from Soviet history. Half of the argument is literally presuming the NKVD hid a substantial amount (itself undeclared in an already weak assertion) of additional executions (with no clear reason to presume why a 'totalitarian bureaucracy' would obscure its own estimates to itself, making its structural violence less effective ['effective' as in socially and ideologically targeting 'the right people,' who were a class minority by nature] as a whole, when that information was [apparently] concealed to the public at large) and then playing numbers games (which is there to draw us away from learning the actual sociological relevance of mass violence and its nature, purpose, and difference between and within reactionary and revolutionary societies). I too could easily misrepresent life expectancy 'discrepancies' (say, of the work done by Amartya Sen) to 'prove' the British Empire starved 200 million people to death in India, but I don't enjoy wasting my time when I know I can't convince people out of their material and social interests. Unlike anarchists, we're not basing our 'arguments' around our petit-bourgeois resentment against political projects that don't require us and were (and are) superior to our baseless (and classless) ideological fantasies. Our arguments are based in a methodology where dialectical and historical materialism have to be internalized, where we have to ask the right questions to even have a chance at giving the right answers. Us arguing about the 'honesty' of the NKVD or the 'possibility' of thousands of unknown shallow graves in Siberia just means that we have already surrendered to the nonsense of our enemies.