(Part 3) Top products from r/vfx

We found 25 product mentions on r/vfx. We ranked the 82 resulting products by number of redditors who mentioned them. Here are the products ranked 41-60. You can also go back to the previous section.

41. The Visual Story, Second Edition: Creating the Visual Structure of Film, TV and Digital Media

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Focal Press

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews42. The Visual Effects Producer: Understanding the Art and Business of VFX

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Focal Press

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews43. The Makeup Artist Handbook: Techniques for Film, Television, Photography, and Theatre

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Focal Press

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews44. Interaction of Color: 50th Anniversary Edition

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Interaction of Color

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews46. Digital Lighting and Rendering (3rd Edition) (Voices That Matter)

Sentiment score: 0

Number of reviews: 1

Used Book in Good Condition

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews47. Nuke 101: Professional Compositing and Visual Effects (2nd Edition) (Digital Video & Audio Editing Courses)

Sentiment score: 2

Number of reviews: 1

Peachpit Press

Show Reddit reviews

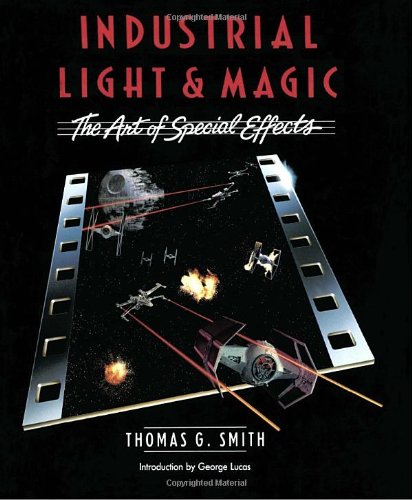

Show Reddit reviews48. Industrial Light & Magic: The Art of Special Effects

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Used Book in Good Condition

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews50. Production Pipeline Fundamentals for Film and Games

Sentiment score: 2

Number of reviews: 1

Focal Press

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews51. Professional Digital Compositing: Essential Tools and Techniques

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews52. Painting With Light

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

University of California Press

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews53. Color and Light: A Guide for the Realist Painter (Volume 2) (James Gurney Art)

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Andrews McMeel Publishing

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews54. Industrial Light & Magic: The Art of Innovation

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

ABRAMS

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews55. The Invisible Art: The Legends of Movie Matte Painting

Sentiment score: 0

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews56. Digital Domain: The Leading Edge of Visual Effects

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Used Book in Good Condition

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews57. The Animator's Survival Kit: A Manual of Methods, Principles and Formulas for Classical, Computer, Games, Stop Motion and Internet Animators

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Faber Faber

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews58. Reflections: Twenty-One Cinematographers At Work

Sentiment score: 1

Number of reviews: 1

Show Reddit reviews

Show Reddit reviews

Hey, while not directly a VFX book, I highly recommend reading this book, The Visual Story, by Bruce Block. I actually took his class back when I was in SC, and I think it's one of my hidden weapons that has given me an edge as a VFX Supervisor. Basically, it's all about how we perceive images on a 2D screen, and the chapters on Depth Cues would help you a lot here.

https://www.amazon.com/Visual-Story-Creating-Structure-Digital/dp/0240807790/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1494700999&sr=8-1&keywords=the+visual+story

Here's my take on where you can go, from back to forward:

Hope this info helps!

So the biggest mistake that a lot of students myself included make, is that they want to get into the really cool stuff first. Animating Spider-man and fight scenes and other bad ass stuff is absolutely why we do what we do. But before being able to do any of that, the fundamentals of animation really need to be hammered in. And the best way to do this is to animate very basic stuff like a ball, or a tail, doing this will help you understand weight and timing. One of the things that I heard repeated constantly in school was that a bouncing ball can be used in most objects, even someone like spiderman. Picture his hips are a ball, and then get the timing of that ball swinging perfect so that it looks like is actually swinging on something. And from there you can start adding more things that make it look real, start animating the arms, then the legs, and the body, and the head. Trying to dive head first with no experience into a complex character will lead to frustration and potentially bad habits.

​

Check out this video on the 12 Principles of Animation, it can seem kind of tedious to learn all of them, but they are all important, some more then others depending on the kind of animation you are doing.

​

For my experience, I started school in late 2011, and it took me 5 years of work to break into the industry after animating constantly. Mind you I was (am) an extremely slow learner with animation, I wasn't good at retaining the information and would constantly blaze past the boring stuff because I just wanted to animate "cool" stuff. I got a job finally last year, and since then I have worked on five different movies, 3 or 4 advertisements including briefly on a game cinematic, and am now currently working on a projected theme park show for one of the biggest theme parks in the world. Being where I am now came with a ton of hard work but also a fair amount of luck and willingness to make friends and connections.

​

If you are serious about pursuing animation and you think you can become passionate about the art and the history behind it, then I would suggest pursuing some form of education in it. There are a ton of online schools with some very talented teachers, and while expensive, they are still cheaper then going to a university.

​

Like I said, it has taken me forever to grasp animation, sometimes I still think the studios are making a mistake in hiring me haha, but I work hard and am eager to learn more. The best advice I can give you is to start basic, work your way up, learn the stuff about animation that only animators can see, and practice as often as you can.

​

Edit: I figure I should mention this as well, a man named Richard Williams who unfortunately passed away just a few days ago wrote what is widely considered the animation bible. I doubt you will find an animator that doesn't own or hasn't put at least some time into reading it. I would highly suggest picking it up, it's called The Animator's Survival Kit, and it's as legendary as he is.

Typically "pipeline" is more like the "glue" that holds all the disparate software packages together, so writing software that does things "off the shelf" software (like Houdini, Maya, Nuke, etc) doesn't really solve by itself. For example:

- allow artists to hand files off to people outside their dept and track which files to use when (so like when a modeler is done and needs to give a model to rigging and then animation needs to pick up the rigged model and then lighting needs to know which version of anim to use) . Some studios use things like Shotgun toolkit for this, others write in house tools, some people use a combination of both. Usually this involves providing import and export ("publish") functionality for off the shelf DCCs.

- facilitate reviews and dailies to allow artists to more easily get feedback on their work

- ingesting plates and dealing with client grades, client side editorial repos, keeping internal cuts up to date with client editorial cuts, delivering finished media back to clients

- at a multi site studio, they may also write the software that deals with keeping files in sync at each facility

​

Studios do also have people who write discipline specific tools or plugins for specific DCCs (e.g. a "2D Pipeline TD" might primarily write tools for compositors to use in Nuke), but the split up of who does what is different by studio (more advanced plugins might be done by a dedicated R&D dept while one-off scripts could be written by any artist, with a discipline specific pipeline TD being somewhere inbetween those two extremes.)

​

I actually did remember that there's a book about pipelines, https://www.amazon.ca/Production-Pipeline-Fundamentals-Film-Games/dp/0415812291 I haven't read the whole thing but it might be an interesting place to start if you're super interested in this topic. :)

You might want to see if your local library has a copy of Dobbert's Matchmoving: "The Invisible Art of Camera Tracking" (also Amazon, Book Depository).

So, there is tracking - identifying features and following them through out the frame - solving - taking tracked features and mathematically calculating the relationship between the features and/or the camera in 2D or 3D. Stable tracking on well selected features allows for more accurate solves.

Chances are that the solving process will provide you with the path of the camera, and locators for the features. Ideally, those locators will show you where those features are in space. All stuff you already know.

You might be able to assume that the level of the tracked ground is consistent and just build it out and see if it holds. It sounds like that is what you are doing already.

There's a few ways you could approach it:

Regardless, what I would suggest is looking at some matchmove showreels - you'll find some really talented artists proving just how good their solves are - often on insane shots - and apply the lessons you take from those reels to your own workflow. eg. /u/semmlerino posted a reel on vimeo.

If you really like it and would like to do stuff like a pro, you should buy a book, IMO there is some books out there that can really boost your game. I really liked Professional Digital Compositing by Lee Lanier. http://www.amazon.com/Professional-Digital-Compositing-Essential-Techniques/dp/0470452617 There's some interviews, a dvd with tutorial and a lot of stuff you gotta know to be a good compositor. Even if you are into motion graphics or anything else, all the basics are in there. Plus, it's a AE and Nuke book and has tutorial on both + some interviews with professional. There is also a lot of other great books and online tutorial are great but doesn't talk a lot about theoretical thing, you gotta understand them by yourself and sometimes, some of them are hard to understand. Otherwise, Video copilot is really great :P

Hi, I would recommend the same book i recommended the digital compositing handbook, I'd also look into Z-Brush, if you like monsters and dive into Artstation.com & Behance.com for motivation and see what people are making.

Unless you are talking about physical VFX, then perhaps history in sculpture and makeup, this book is great https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0240818946/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_search_asin_title?ie=UTF8&psc=1

I bought that book for learning how to retouch photos better. The theory of lighting and shapes is very good.

No problem.

A solid understanding of python & logic also helps, but 90% of the dicking around you'll be doing will be in VEX, which is pretty much just vector math.

The handy thing about Houdini is that geometry operators and shaders are both written in the same language, so you can prototype operations in SOPs and then copy/paste the code/VOPs to the shader context and as long as you remember to handle the space transforms (shaders default to camera space, SOPs default to object space) everything just works.

This masterclass on fluid solvers is fantastic, it's what made DOPs really click for me, this is a good example of the math;

https://vimeo.com/42988999

Other books worth reading;

https://www.amazon.com/Fluid-Simulation-Computer-Graphics-Second/dp/1482232839/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1480804002&sr=1-1&keywords=fluid+simulation+for+computer+graphics+second+edition - full explanation of how fluid solvers work internally, probably overkill for most artists, but helpful if you want to break things, namely FLIP & Pyro.

https://www.amazon.com/Advanced-RenderMan-Creating-Pictures-Kaufmann/dp/1558606181 (this is quite old and deals solely with the old REYES algorithm, but contains a lot of information on how renderers work internally and a lot of it applies to VEX, which was designed to be very similar to RSL).

https://www.amazon.com/Physically-Based-Rendering-Third-Implementation/dp/0128006455/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1480803895&sr=1-1&keywords=physically+based+rendering This is an explanation of the workings of physically based renderers, but it's quite heavy going.

The bad news: There are mountains of legal issues and risks an artist takes on with sharing that kind of information. Also there are many of variables from company to company, project to project: rendering package involved, in house tools, required techniques involved, client demands, time/money resources, final look goal, delivery specs, etc. Even if someone could provide production scripts, these factors make it an ineffective and possibly detrimental approach to learning.

The good news: You can start learning in much more effective ways that will actually prep you better for production! I agree with Bootylicious overall, in that you're going to get the most from making your own projects and learning to problem solve them as you move forward and hit unforeseen hurdles. Doing is the biggest, the most challenging, and the most important part.

With that said, it's not always enough to just keep trying without being equipped with the proper knowledge, you'll eventually come up against issues you can't solve just by pushing without outside information. But it won't be specific scripts that get you through these times either. Core, software agnostic, concepts are going to push you through your biggest obstacles and help you learn to ask/answer critical questions:

What image do I have? What do I want it to be? What are my resources? What approaches do these 3 answers allow for?

Assume that every company, every client and every project you encounter is going to be totally different, so learning to answer these will help make you a flexible, comp-rock-star.

Make a project with as clear of a goal as you can and start there, when you get stuck, or as you go along in general, learn from software agnostic sources that focus on the skills and theory, over sources that focus on a specific program.

I've included a few book links below + happy comping!

https://www.amazon.com/VES-Handbook-Visual-Effects-Procedures/dp/0240825187/

https://www.amazon.com/Digital-Compositing-Film-Video-Production/dp/1138240370

https://www.amazon.com/Light-Visual-Artists-Understanding-Design/dp/185669660X/

Ron Brinkmann's book should be required reading for compositors, pretty much (and probably is if your course has a reading list).

Also has 100+ pages of case studies.

It's kind of a weird question though. Their work is shown in the films. I assume watching Blade Runner doesn't count towards your credits? If you're researching the technical aspects (ie the "how"), sites like fxguide have interviews on how they made stuff from a vfx standpoint, and the thousands of "making of" featurettes and videos.

It sounds like you're looking to research the artistic considerations (the "why") however. Which is why it's weird because it's generally not vfx making those decisions, and certainly not one single compositor you can reference. It's directors / cinematographers, and is deeply rooted in photographic composition. Reflections is a good book for looking into that.

Color and Light - yes it's a painters book but the theory and ideas apply directly into compositing. (http://www.amazon.ca/Color-Light-Guide-Realist-Painter/dp/0740797719)

Digital Compositing for Film - You are going to hear and read a lot fo stuff by Steve Wright. He basically is the man haha. This book is great because it teaches ideas no programs. EVERYTHING YOU COULD POSSIBLE NEED TO KNOW ABOUT COMPOSITING IS IN THIS BOOK!(http://www.amazon.ca/Digital-Compositing-Video-Steve-Wright/dp/024081309X/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1413392563&sr=1-1&keywords=digital+compositing)

For your last question, I did a while ago, i didn't work for them I worked with them. I now am employed by Prime Focus World.

At this stage, what you should probably do is lock your script, create storyboards for the vfx shots/sequences and then put together a breakdown of the vfx shots you have plus the storyboards and send this breakdown out to several vfx studios to get bids for the work (and also the cost of having their vfx supervisor on-set). This book will give you a better idea of the vfx bidding / budgeting process

https://www.amazon.com/Visual-Effects-Producer-Understanding-Business/dp/0240812638/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1465510338&sr=8-1&keywords=the+vfx+producer

Also, you should find out if your film is eligible for any vfx tax breaks such as the DAVE tax credit in Canada. Those tax breaks can be significant and could influence you to go with a vfx studio in a certain country or state.

Visual Effects: The History and Technique

Pretty much what it says on the tin, and what you're mostly looking for as a broad overview. It isn't completely up to date -- a lot has changed just in the six years since its publication -- but as far as history and lineage goes, it's the gold standard.

There are also some books focusing on particular major houses that also contain solid general background:

Industrial Light & Magic: The Art of Special Effects

Industrial Light & Magic: Into the Digital Realm

Industrial Light & Magic: The Art of Innovation

Digital Domain: The Leading Edge of Visual Effects

The Winston Effect: The Art & History of Stan Winston Studio

For the most up-to-date state of the art and industry, you can't go wrong with Cinefex, and as far as history lessons go, get a hold of as many backissues as you can. The entire catalog is coming to iPad early next year.

yep, that's sound advice. One of the best books on lighting has nothing to do with CG.

http://www.amazon.com/Painting-With-Light-John-Alton/dp/0520275845

http://www.theasc.com/blog/2013/10/07/john-alton-cinematographys-outlier-part-one/

You should consider checking out the OpenGL "Orange book," ie. OpenGL Shading Language. It's pretty much THE book to know when writing your own shader. Some of the information is a little bit dated, for example, it doesn't give specific examples on normal maps, but it teaches the fundamentals behind normal maps. It's an incredibly useful reference.

Joseph Albers' Interaction of Color is great: https://www.amazon.com/Interaction-Color-Anniversary-Josef-Albers/dp/0300179359

That's a pretty heavy book. A more practical book would be,

digital lighting & rendering 3rd edition

The Invisible Art is the most famous piece of illustrated content about matte painting (so... set extension)

There is not a lot to say about methodology... production designers build a set in accordance with the director, scripts, concept artists and budget. The scope of the scene might require bigger sets than the production designer can build under budget. So the build is kept to a minimum and the VFX team comes in to "extend" the set to match the directors vision. Back in the days this required a locked camera and a matte painter would come in to paint - possibly on glass- the added elements, but nowadays it happens completely in post, digitally.

The camera movement from the plate is analysed by match movers, a LIDAR scan might be used to reproduce a high density mesh of the scene, a 3D version of the scene is inferred from this data. The digital matte painters (names vary depending on the company they are in) model extra geometries, paint details, patch trees in the background... whatever is necessary to build the end shot. This is then rendered one way or another through the shot camera and compositors work to smoothly blend the real plate set with the CGI one, using all the tricks in their bags. Not sure if this answers your questions.