(Part 2) Best central africa history books according to redditors

We found 166 Reddit comments discussing the best central africa history books. We ranked the 42 resulting products by number of redditors who mentioned them. Here are the products ranked 21-40. You can also go back to the previous section.

21. Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa

1 mention

Part 1

Sorry to come back with some 'hairsplitting', but your questions are so 'broad', they would require a host of definitions and extremely 'broad' answers. It's like you've asked how many wheels are there on some train - without explaining what train, what locomotive and how many cars...

Up front one must understand that 'Africa' is one continent, but not a single nation. Sub-Saharan Africa even less so. Indeed, not a single nation there consists of just one ethnic group, which in turn means there is a host of different nationalities, ethnic and religious groups, etc., which in turn means there is an even wider range of political systems, and military traditions - and experiences.

Thus, when you ask,

> Have any new lessons come from this conflict?

One can only answer with such 'idiotic' replies like: Yes, a host of new lessons - but from what conflict, please? There are about a dozen raging alone in the CAR, DRC, Rwanda and Burundi - alone - since something like 70 years...

> How competent are the forces involved?

Some are 'hypercompetent', and others full of such suppositions and prejudice like 'bullets can't kill a white man', or the crack from firing a fire-arm can kill one too... It all depends on whom do you want to discuss, i.e. what is the conflict on your mind?

> Particularly in and around the Congo area, Subsaharan Africa has seen quite a bit of extensive, low-intensity guerrilla warfare conducted by a plethora of state and non-state actors. How have the strategies and tactics of the various actors involved changed over time, have observing nations learned anything new about this sort of fighting?

Essential problem with the DR Congo 'area' is Rwanda. In the case of Rwanda, one could monitor a period of 'no development at all' in regards of doctrines and strategies for decades (so also in regards of 'low-intensity' and 'high-intensity' guerrilla warfare), then a period of 'intensively evolving' doctrines and strategies in the 1990s, and then again 'no development at all' since around 2001-2003.

The essence of the 'problem' there is of ethnic nature: there are two major ethnic groups, each convinced it's superior to the other - and that primarily thanks to the ideologies developed by their former colonial masters. Moreover, and more recently, one of the groups was misused by the USA and Israel to take over the country and convert it into 'Israel of Africa' in order for private interests in the USA to get their slice of what certain Henry A Kissinger titled with something like 'Congo's 35 trillion fortune', 'but' was considered for something like Franco-Belgian turf until 1990s.

So, in 1990, a large chunk of the Ugandan military - about 5,000 of people predominantly Tutsis that grew up in refugee camps in that country - launched an 'insurgency' against the (not really) Franco-Belgian supported Rwandan government. That 'insurgency' was de-facto a Ugandan-supported invasion (subsequently supported by numerous US and British private interest groups), that was anything else than 'guerrilla war': actually, thanks to the rivalries between top leaders of the insurgency (which culminated in a quick assassination of one of them), but also much more powerful (and far more competent) resistance of the regular Rwandan armed forces, it quickly degenerated into little else but trench warfare. That's where it remained for most of the next four years. Then, the 'hawks' within the Hutu majority of Rwanda lost nerves and the situation degenerated into a genocide of not only the Tutsi, as usually reported in the West, but also plenty of the Hutu (in which the 'innocent insurgents' were greatly involved; for details, see Rwandan Patriotic Front).

Once the 'insurgents' have secured Rwanda, they realized that over 50% of the population fled, and the country couldn't survive on its own. It had no economy, nothing to live from - even more so without the population. Thus, they launched a 'spontaneous repatriation' of the refugees from the Eastern DRC, (called Zaire from 1972 until 1997) in 1996... only to find out that there's actually no Zairian military to stop them. They 'spontaneously repatriated' about half a million of people (massacring dozens of thousands in the process), while quickly sacking the few Zairian units that offered resistance. That resulted in the Rwandans finding out they're now in control of quite extensive mines of such stuff like gold, diamonds, koltan etc. ....and that there is even more of the same if they go further west.

Thus, with the excuse of 'pursuing the genocidaries' a country the size of New York City, launched an invasion of a country the size of the USA east of the Appalachian Mountains... and actually, and with some help from Uganda, Zimbabwe and then Angola (the leaders of all of which had similar $-signs in their eyes), managed to topple Mobutu, in May 1997 (this despite some French attempts to organise some kind of a mercenary army consiting of Serbs, few Belgians and a handful of South Africans). Although officially run in the name of the 'AFDL-guerrilla' led by small-time Marxist-cum-businessman named Laurent Kabila, this was actually also no 'guerrilla campaign'. Rather a quite conventional military advance through the jungle, with plentiful of commercial air power support.

By 1998, what a surprise, Kabila found out he can rule at least Kinshasa on his own, and turned anti-Rwandan. 'Deeply depressed' (quote from certain Major-General James Kabarebe of the 'Rwandan Defence Force'), the Rwandans then staged a counter-coup: they hijacked several airliners at the (Congolese) airport of Goma, and used these to airlift a force of several thousands of their and Ugandan troops all the way to Kitona Air Base, on the Atlantic coast (about 1,500km away from Rwanda as the crow flies). From there, Kabarebe launched a (quite conventional, actually) advance on Kinshasa, his troops looting, pillaging and killing as they went.

'However', in the meantime, Kabila reached an agreement with Zimbabwe to deploy its troops to 'monitor the Rwandan military withdrawal from the DRC'. So, the Zimbabweans landed at N'Djili International - only to find themselves under a combined Rwandan-Ugandan assault, a few days later (that was in August 1998).

Although hopelessly outnumbered, the Zimbabwean military of that time was still one of most professional and combat experienced military in all of Africa. Unsurprisingly, its paras, SAS, and air force smashed Kabarebe's force to bits and pieces - in something like two weeks of trench- and then house-to-house warfare down the runway of N'Djili (you can read about that episode here), and then down the slums of N'Djili... Kabarebe and his survivors then withdrew into northern Angola, from where they were extracted on board Victor Bout's 30+ years-old transports, on Christmas Day....

But, I digress: the rest of that war was also no 'guerrilla war', but a perfectly conventional war. For details, see Great Lakes Conflagration.

Now, around 2000 or so, Kabila's son Joseph took over and quickly came to a very good idea: WTF fight the Rwandans conventionally with his unreliable military, and drain the drained Zims even more? Why not mess around in the Rwandan backyard? Thus, he re-organized the militia of the Hutu refugees (i.e. what the Rwandan 'democratic' leadership calls 'genocidaries'), and deployed it into the Kivus (meanwhile some 600km behind the frontlines). That was a guerrilla war, and the Hutus lost heavily. But, the idea was sound. Thus, Kabila then started using diverse other of local minorities - like the Maji-Maji - which wasn't hard, because the Rwandans were meanwhile applying Soviet/Russian style COIN upon the local population (see: loot, rape, kill and torch everything in your way). Unsurprisingly, there are estimates about up to 5 million of the Congolese massacred by the Rwandans, Ugandans, and their local allies by the time...

But, the fact was: the diminutive Rwanda was simply overstretched in the DRC - even more so once its commanders began quarreling with the Ugandans over the profits from gold mines around Kisingani and the two allies started fighting each other. Thus, between 2001-2003, the Congolese insurgency really ruined the Rwandan plots in the eastern DRC, eventually forcing Kagame to accept at least one of some 15 cease-fire agreements negotiated by the time and, finally, withdraw from the DRC. At least officially.

(to be continued...)

Shinkolobwe is a tough subject to talk about as there is very little research currently done on it, but I will share what I know so long. I am hoping to delve further into it once I have finished my current projects and will post more info on it eventually.

Essentially, the Shinkolobwe uranium mine in Congo dates back to Belgian Congo (1921 onwards) and was the mine from which uranium for the Manhattan Project and the bombs dropped on Japan was gathered. The mine was officially decommissioned in 2004 but apparently still operates in an "artisanal" fashion - which just means it is being mined illegally but with the government turning a blind eye.

Very few people stop to think about where the uranium used in atomic weaponry comes from, but in the early days, most if not all of it came from the Congo - as did much of the copper used in WWI! The scale of the horror the unprotected miners suffered as a result of handling raw uranium is only now being explored - and atrocities surrounding Congo's resources are still happening today! But I digress, as we are meant to stick to the historical aspect here.

From a military history point of view, the story behind this mine is fascinating and how it intertwines with WWII logistical supplies as well as early Allied and Axis attempts at studying the chain reactions behind uranium (eventually leading to the development of atomic weaponry) is fascinating. Further, just how involved Congo was in supplying other resources to the West and the East from the early 1900's until even today is still worth exploring.

I'm sorry I can't go into further detail, I have a lot of work to take care of - but I will provide plenty of reading material below if you are interested:

---

There is a good book by Susan Williams called Spies in the Congo : America's atomic mission in World War II which explores this topic at length - though the main criticism is that there is significant speculation throughout the book (which is understandable considering the scarcity of records in Congo of the mining activities - as well as the classified nature of the documentation in the US, Belgium and UK).

I also recommend these articles if you wish to read further:

Adamson, M (2017) The secret search for uranium in Cold War Morocco

Currier, R.H. (2002) Into the Heart of Darkness: searching for minerals in the democratic Republic of the Congo

Jalata, A (2013) Colonial terrorism, global capitalism and African underdevelopment: 500 years of crimes against African peoples

And further:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-radioactive-cut-that-will-not-stay-closed/

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/sep/17/spies-in-the-congo-susan-williams-review

http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/7/23/in-congo-silence-surrounds-forgotten-mine-that-fueled-first-atomic-bombs.html

Not an article, but King Leopold's Ghost is a great book, as is The Congo: From Leopold to Kabila

Or if you have an hour to kill White King, Red Rubber, Black Death is a very well made documentary.

I don't know how obscure the conflict is, but the Congo Wars are definitely less well known than they should be. Dancing in the Glory of Monsters is a fantastic book which is engrossing and very easy to read. Available on Amazon. Africa's World War is another excellent but more academic/dry book about it. Also widely available.

If anyone is interested in learning just how evil the LRA is, I recommend the book First Kill Your Family: http://www.amazon.com/First-Kill-Your-Family-Resistance/dp/1556527993/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1318631767&sr=8-1

I don't use the word evil lightly, but recruiting child soldiers and having their first order be to kill the rest of their family is evil.

If you want to read a cool story about "regression" of a once civilized place, check out a book called "Blood River", about the Congo. Not a great book, but a very interesting story.

Check out the first review on Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/Blood-River-Terrifying-Journey-Dangerous/dp/B0033AGSTG

Slave trading was already going on in West Africa by the time Portuguese Explorers began going on slave raids into the Senegambia coast in 1444. Keep in mind the "slave trade" we think of today, with a well assigned system, rules and way of treating slaves already in place. Slaves where gained by raids and through war, to which they where often put out to work, though treated much better than the Europeans did, most slaves where used as servants and used for manual labor, though given much better nourishment and treatment.

Many slaves would be treated as part of the family once enslaved, and would be allowed to eat and stay in the house of whoever family they where with. Slaves would be traded though, usually to lend off their talents or to just gain money.

When the Portuguese arrived in 1444 they sent out slave raids on the Senegambia coast, somewhat successfully until West African (Mali) forces began naval scrimmages against the portuguese vessels, often using much lower quality boats, yet, due to their skill with poison arrows where able to put the Portuguese in an increasingly tough situation until in 1456 they send Courtier Diogo Gomes to establish peace between Portugal and the Senegambia coast ruling Mali Empire (though the empire was in its decline, soon to transform into the Songhai empire)

in 1462, after peace was established, Portugal shifted its focus from raids and battles to trade with the Africans. Still desiring the original recourse they came for, slaves, they heightened demand greatly. The West Africans, seeking the valuable European goods began heightening their slave trade, taking slaves from rival nations and villages to be sold to the Europeans.

The Africans (those not being enslaved) and Europeans both prospered off of this, West Africans became wealthy off of the trade of rival nations and slave trade blossomed as a great new economic tool was established.

In short, the modern thought that Africans where "Enslaving their own" is incorrect. Slaves came from enemy and warring clans and nations, as separate culturally and individually as, say, Vietnam and China. This meant west african nations could now profit from war and battle with their rivals, and that they did. They where quite willing to trade with European partners due to the great goods the Europeans offered, and they traded slaves by their own free will. It was like any other business in a sense. Slaves already owned where traded to Europeans and more where captured after that. It was a mutually beneficial economic relationship, though it damaged the relations in west Africa greatly, throwing the nations into a time of constant tension.

---

Sources:

[The Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali and Songhay: Life in Medieval Africa | by Patricia McKissack and Fredrick McKissack] (http://www.amazon.com/Royal-Kingdoms-Ghana-Mali-Songhay/dp/0805042598/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1414292037&sr=1-1&keywords=Mali+%28Empire%29)

The African Slave Trade | By Basil Davidson

https://www.amazon.co.uk/PRECOLONIAL-BLACK-AFRICA-Comparative-Political/dp/1556520883

I have not read this but a professor recommended it to see the difference in African and European society

In addition to what was already recommended to you, if you can, I recommend getting your hands on Barrie Collins' Rwanda 1994: The Myth of the Akazu Genocide Conspiracy and its Consequences. Collins was a member of the (British) RCP (a Trotskyist group) before it disbanded itself. You might also be interested in Rwanda and the New Scramble for Africa: From Tragedy to Useful Imperial Fiction by the Québécois nationalist Robin Philpot.

Hint: all these books are available in pdf format (if you know where to look), but I would recommend buying a real copy to support the authors.

http://www.amazon.com/Sudan-Religion-Violence-Short-Histories/dp/1851683666/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1418285087&sr=1-1&keywords=jok+sudan

> What we call bias, is another way of describing our individual way of seeing the world. Knowledge can make this more clear, but always how I see things, is different to how you see.

We have been talking past each other on this matter. My understanding of "bias" is grounded in the cognitive science literature founded by Kahneman and Tversky, it is a veritable buffet of precisely defined inadequacies. Your use of the term "bias" appears to be very close to my use of words like "subjective", or "implicit", or "personal". I would pay dearly to alleviate the former, just as I would pay to retain the latter.

> I would be glad if you would share your thoughts about these ideas of mine in regard to faith and love as the only epistemology of knowing about God.. It is not an idea I have heard from someone else, but something of my own creation, so it is difficult to judge the solidity of its veracity on my own.

While I have heard similar conceptions in my journey (as the writer of Ecclesiastes says, there is nothing new under the sun), I accept and am impressed that it is independently originated by you. While I'm unclear how productive this line of inquiry will prove, allow me to generate a response.

I would first like to hear the mechanism elaborated in greater detail (a motivating question could be: what epistemological methods does this idea of love entail?)

But the shape of my response is unlikely to change, provided your conception of love is not terribly surprising. And that is that all human relationships that participate in love do not occur in an empirical vacuum. Rather, all such human love-heuristics are contingent on visceral evidence.

To use an analogy: I allow myself to love my siblings because I have vivid memories of our childhood together, memories that can be corroborated by sense experience. I would not love them if I had not first developed very strong reason to not doubt their existence.

This is one reason why I am uncomfortable applying your love-heuristic to theology: because I feel no such assurances that God exists. I am willing to expand my existence-affirmers beyond sense data (I would consider theism if I thought its many metaphysical arguments worked). But I find myself wanting to only apply my socially-oriented love-heuristic once I am assured that a recipient exists. It seems to me that to decide otherwise is to open oneself up to self-deception.

>> the physicalist must explain how physical events map to mental phenomena.

> You will need to do even more than this. The same problem of interaction you ascribe to substance dualism applies here. Even a complete map of neural correlates will not suffice for explanatory power. You will need to explain how these physical events will cause phenomenological properties. The two are not identical, so then I can point to no physicalist explanation of mechanism of interaction, but also no account of mechanism of production.

I'm realizing now that I was using an abnormally broad notion of mapping. We are in agreement. NCC maps are distinct from explanation.

> What will you make of our intuitive linguistic preference for substance dualism?

Ah, incisive question - my sentence before had failed to consider this fact. I would appeal to Metzinger's appeal to transparency: the interface between our mental modules and our self-models are so efficient they appear contiguous.

> I would propose that [folk psychology] is at present a more accurate predictor of behaviour than any tool of cognitive science. Necessarily again faith enters, we can only know each other with faith or trust that what you tell me, or what you do, is a true description of your inner life. How will cognitive science ever conquer this fact?

I don't think there is a fact to conquer: cognitive science performs much better than folk psychology when it comes to prediction. This is, of course, a very broad claim, but one I could coat with an arbitrary amount of evidence. I can start with the remarkable successes of clinical psychology, and how they are unparalleled to any tradition grounded in folk psychology. I would also note that the bystander effect is something predicted by cognitive science, but consistently surprises laymen versed in folk psychology.

> [Theoretical innovation] is surely happening now and hope you will not judge the truth of our side too harshly for this point only.

I won't.

> the quantum subject is not so much my interest.. Your lesson has taken root, because my mind is now saying I will need to apply the same skeptism to what you are telling me [about QM physicalist interpretations]!

I would advise caution here. Taking my words with a grain of salt is a virtue, but skepticism mixed with incuriosity is a System 1 defense mechanism. This response to my argument about the diversity of QM interpretations is distressingly similar to that of a Zande responding to criticism of his systems of oracles.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/d/cka/Bitter-Harvest-Great-Betrayal-Ian-Smith/1857826043/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1485718097&sr=8-1&keywords=ian+smith

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Rhodesia-beginning-end-Ron-Morkel/dp/145378943X/ref=pd_sim_14_3?_encoding=UTF8&psc=1&refRID=X40MRKAQ87XGC55146MF

Well, so far I've read (well, finished, I'd started reading it in December) Anglo-Norman Warfare, which is a collection of essays edited by Matthew Strickland (recommended on the /r/WarCollege reading list), and Black Hawks Rising by Opiyo Oloye. I'm now reading the British Museum Anglo-Saxon Art book by Leslie Webster. I'm hoping to finish that fairly soon, and get started on Tank Warfare on the Eastern Front 1941-1942 by Robert Forczyk.

In terms of mini reviews:

-Anglo-Norman Warfare is very interesting, especially the second half. There's a lot of different academics writing in it, and they're often hilariously vicious to each other.

-Black Hawks Rising is an incredibly interesting book, but I did struggle with the way it's written. Some serious editing needs to be done. I also don't really know enough about the individual armies involved in AMISOM to be able to assess the author's regular tendency to refer to (for example) the Ugandan army as "highly professional". I wouldn't mind somebody's input on that, if any of you are more knowledgeable than I am.

-Anglo-Saxon Art is good, and has a lot of very good pictures to accompany the text. It is an Art History book though, which means I'm less at home with the terminology.

I wouldn't mind if anybody has anything to say about the Robert Forczyk book before I read it!

Found it: Silent Accomplice: The Untold Story of France's Role in the Rwandan Genocide by Andrew Wallis.

Totally worth a read.

Sorry for late response. The book "A Modern History of the Somali: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa" talks about Somali clans and origins.

Dancing in the glory of monsters by Jason Stearns.

After starting, I cancelled plans that weekend so I could stay in and read it.

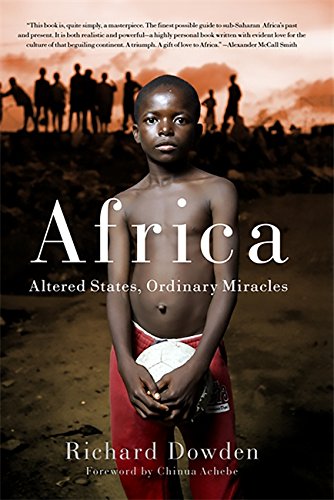

Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles was a good book on post-independence Africa. Has a good treatment of Zimbabwe, Sierra Leone, Congo, and Nigeria.